Home » Portfolio Management

Category Archives: Portfolio Management

Book Review: Volatility Trading

This is a book about trading volatility professionally. The target audience is those who already have some familiarity with options theory and are ready to use math in their market analysis. One does not need to be a professional options trader but the book instructs a professional attitude toward trading.

It accomplishes two goals very well. First, it delivers a set of knowledge about volatility markets. Second, it delivers the message that trading is hard and demands deliberate focus. So while the actual material is on the volatility markets, the theme of the book is that one should use all of tools at our disposal, use a systematic methodology and target continuous improvement. In short, if you wish to learn about volatility trading or, in general, how to approach trading of any sort as a business, you will benefit greatly from Volatility Trading. This is not idle talk. I ran an options trading desk and purchased a copy for each person working for me.

Despite having a PhD (yes, despite) and including the relevant math, Sinclair is clear and overwhelmingly practical. Even for those that already trade volatility products, as I do, there is much value in the material. He does much work for us, including:

1) Reading a vast amount of academic and industry research, as well as conducting his own; then highlighting the most valuable nuggets.

2) He puts into clear prose and practical context those most valuable results. For example, the explanation of why leveraged ETF’s erode in value but are not “destined to go to zero” was illustrated nicely with text that complemented the math. Math is necessary and adds to the explanation.

3) He puts the theory into the context of practical reality. Although this is most obvious when he discusses the shortcomings but utility of the Black-Scholes framework, it comes through elsewhere such as under what circumstances higher efficiency estimators fail back into the daily close-close estimator.

That said, there is subject matter relevant to volatility trading that is not covered but still important to volatility trading. For example, volatility options (VIX options) or dealing with portfolios of options. The subjects covered are, for the most part, covered well – the section on behavioral finance is, understandably, given only a quick run through. Even in this section, the practical nature of Sinclair’s outlook shows through as he discusses that we should mind our own foibles for mistakes but also look to those same foibles for sources of potential edge.

From the perspective of trading as a professional, Sinclair bangs the drum on:

1) Quantify what you can.

2) Remember #1, but using non-quantifiable information is valuable and, often, necessary.

3) Understanding that trading, particularly options trading that is so path dependent, is about playing the probabilities. Keep the long run in mind.

4) Trading requires having an edge; to best exploit it, understand it and the tools you use.

5) Emphasize the practical, particularly developing a process.

I cannot provide a review of the web site as I have not yet used it.

I will conclude with Sinclair’s own words: “Successful trading is about developing a consistent process.” Knowledge is essential but insufficient. I think that is what Euan Sinclair would hope the reader came away with and kept. Everything else can be researched – and much of it can be found in “Volatility Trading.” I find it very valuable and highly recommend it.

If you enter Amazon through my site (the image above), I will get a small commission. I am experimenting with this as a source of revenue for my blog. Hopefully reviewing the book (and my other posts) added some value. If so, great. Incidentally, the commission is already built into Amazon prices and the price stays the same whether you enter from my site or not.

Yield Trek: Into Darkness, Part 2

“Random chance seems to have operated in our favor” — Spock

“In plain, non-Vulcan English, we’ve been lucky” — McCoy

“I believe I said that, Doctor” — Spock

The data shows that there have been large inflows of cash to yield bearing equity strategies. That is not enough to get worried. What I’d like to see before shorting is 1) elevated prices & valuations, 2) an illusion of safety, 3) feedback loops, 4) diminishing ability to put cash to work and 5) a catalyst. Fortunately, we are able to see all of these things in this yield trade.

Valuation: danger ahead for REITs

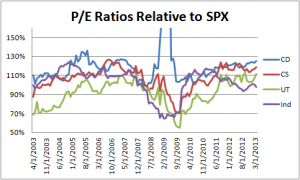

I first look at the data for non-REIT companies. Above is a chart showing price-to-earnings (P/E) and price-to-book (P/B) data for 4 heavily weighted dividend sectors. Those sectors are: utilities, consumer discretionary, consumer staples and industrials. These are GICS sectors and the data is from Bloomberg. The utilities P/B ratio is quite high. Bluntly, P/E ratios look relatively normal. However, take a look at the next graph showing revenue, earnings per share (EPS) and debt per share. Note:

1) consumer discretionary revenues have not caught up to pre-2008 highs, but EPS is significantly higher

2) revenue and EPS are higher for consumer staples, but debt/share is growing and is double pre-2000 levels

3) despite languishing revenue and EPS, utilities debt/share are at all-time highs

I’ve included another graph showing P/E ratios relative to the SPX P/E. Other than industrials, all of these four sectors look, at least, slightly rich. Utilities, in particular, looks very expensive compared to alternatives in the market. Overall, it looks clear that investors are overpaying for sectors considered to be dividend payers though not necessarily at nosebleed prices. Utilities valuations and debt burdens are showing definite warnings signs and should be avoided, or used as a candidate for the short side of sector pair trading.

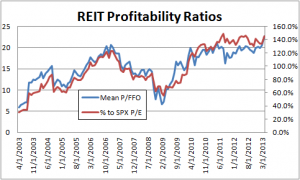

REITs are a different story. I’ve kept them separate because they use a different profitability metric, P/FFO. The data for this article is from Bloomberg and I was unable to get historical FFO data for the S&P REIT Index directly. Instead I took 5 major REITs (BXP, AVB, SPG, KIM, VNO) and aggregated the data. I took simple averages of their P/FFO ratios; not all series went back to 2003 but the latest started 2005. As can be easily seen, on both absolute and relative bases, REITs are at their highest profitability ratios in the last 10 years including during the real estate bubble.

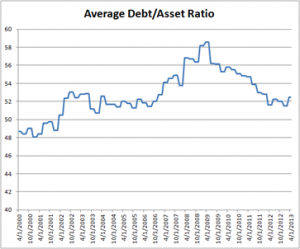

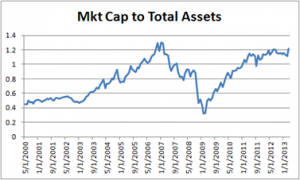

On the surface, it seems as though REITs have cleaned up their debt act a bit since 07/08. However, the reason for the peak of the debt/asset ratio in 2009 was due to the precipitous decline in the value of assets. Now with assets stabilized and even increasing, REITs have increased their debts so that the ratio is back to pre-crisis highs. In addition, the market is giving them an extremely generous market valuation for those assets. Market capitalization, for at least those major 5 REITs, is right back to pre-crisis, i.e., bubble level, highs. REITs are squarely in the danger zone based on valuation.

Illusion of Safety

With the exception of high yield bonds and, possibly, MLPs, dividend and low volatility strategies are touted as being safe (for example, here or here). But the safety that is being offered is measured using the rear-view mirror. Safety is being judged based on past performance – which we know is not a guarantee of future results. Measuring risk based on historical asset movements has three major flaws. The first is that it is measuring movement, not risk. For example, standard deviation does not differentiate between assets bouncing around and an earnings release that qualitatively changes a company outlook. Second, it does not account for asymmetric risk. Option positions are one type of asymmetric risk; buying an asset very cheaply or paying too high a price is another. Third, it creates feedback loops when large amounts of money move based on the same criteria. Low volatility invites larger asset purchases, particularly with leverage. This decreases realized volatility as prices move up which again invites larger purchases. Once inflows inevitably stop, volatility increases, causing risk reduction or margin calls as exposures must be managed based on newly assessed risk outlooks.

Low-volatility investing works by measuring prior period asset movement, much as Value-at-Risk (VaR) does. SPLV, the largest low volatility ETF, bases its holdings on realized volatility over the prior 12 months and rebalances quarterly. The nice thing about low volatility asset management is that it is based on solid empirical data. That’s good except for the part about how the data that was used for the studies did not count on large amounts of money following the same strategy. SPLV does not count on anything else other than qualifying as the 100 stocks out of the SPX with the lowest realized volatility. These assets tend to look like traditional dividend players – and heavy on REITs (10% for SPLV, less for others). If these holdings begin to get volatile, they will be forced to evict them from the portfolio which will then contribute to greater volatility.

Feedback Loops & Diminishing Ability to Buy More

In addition to the volatility based feedback discussed in the section above, there are other feedback loops at play:

1) Margin debt. Discussed here, note that the most recent release which was subsequent to that post, showed margin debt climbing to an all-time high.

2) High levels of bond funds holding equities. Discussed here.

3) Risk parity and similar strategies. Discussed in part 1.

4) Abenomics leads to Yen devaluation and Japanese “exporting” deflation. here and here. With Yen depreciation at least temporarily slowed, expect Japanese money to REITs to slow or stop.

5) One of the most interesting feedback loops also comes from Japan, where they, too are searching for high yield. In the Heard on the Street column from April 15, 2013, it was reported that Japanese investors have been searching for yield in vehicles that invest in US REITs. The key part is that they pay out unrealized (not a typo, unrealized) capital gains on the way up as dividends. That is amazing. One can only imagine the debacle if US REITs stop climbing. Oh yeah, and they are large holders of these stocks, too. According to the article, they own 8.6% of SPG and 10.1% of VNO. For those of you that remember chemistry class, this reminds me of a super-saturated, barely stable solution ready to blow (think Diet Coke & Mentos).

Catalyst

This is the toughest part about investing. Even if one presumes enough to believe that one has the correct analysis, it is no good to be too early (e.g., Abnormal Returns from 2011). What might be a catalyst could turn out to be a bump in the road. That said, I believe that we have seen the catalysts to shake things up. First, FX market volatility has picked up. After hitting multi-year lows at the end of 2012, the JP Morgan global FX volatility index has rebounded to 2010-2011 levels. This is due to Yen weakening. Second, that volatility has spilled over into commodity markets, most noticeably gold & silver. I consider this to be a canary in the coal mine. Finally, the potential for the Fed to slow or stop purchases in the mortgage markets will have a huge impact on volatility and asset prices. Fixed income prices have begun to re-price the possibility of this and it has sent 10 year note yields to their highest level since beginning of 2012 in just a few sessions. Recall too that the Fed effectively sells volatility by buying mortgage paper (there is an embedded pre-payment option).

Conclusion

All well and good, but what is the elevator speech? Too much money, most seemingly leveraged money, is chasing the latest investment craze – yield in dividend stocks. The most distended market is for REITs which looks particularly expensive by benchmark measures. Further, the investor class in REITs is a large set of “weak hands.” That is, they are investors who will need to exit (due to margin calls or structural investment guidelines) at the first sign of trouble and they are too large a proportion of owners to make the exit orderly. While other areas of dividend investing may look rich, REITs are where the focus should be for short ideas. The time is soon approaching when this will occur – already some volatility has been creeping into REIT shares and ETFs. It is hard to imagine that continued inflows will recur. And once the support for an overvalued asset stops, the decline can begin.

Yield Trek: Into Darkness Part 1

“Mr. Spock, the women on your planet are logical. That’s the only planet in the galaxy that can make that claim.” – Captain Kirk

This post has taken far longer for me to put together than I had anticipated. I spent quite a bit of time putting together the data and moving down paths that didn’t work. It is also taking more text & space than I had anticipated. Therefore I am splitting this into multiple posts. This first post covers the explosion of assets in yield bearing equities. One last editorial note, substitute “investors” for women in the quote above.

In at least on respect, FED policy is working: QE via its bond buying program is forcing investors up the risk curve. And that is making for an unintentionally very over-crowded trade. This is because multiple trends are coming together into the same or similar assets due to investors’ search for yield and safety. It is the natural reaction investors have to getting burned twice before reaching for capital gains: first in 2000 with dotcoms and in 2008 in real estate. Rather than seek capital gains, they are trying to play it safe by being content to collect dividends. But investors are paying high prices for small cash flows and the quest for yield is playing out in bulk. If this plays out as another crash as I expect it will, the irony will be that investors were trying to be conservative.

Here are some of the trends:

– Dividend stocks

– REITs

– MLPs

– Preferred stocks

– Low-volatility investing

– Risk parity investing

– Yen depreciation

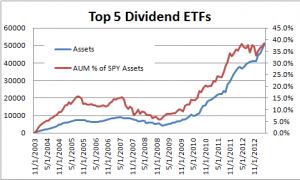

It’s easy to see how a quest for yield leads investors to these first four sectors of the stock market. Even bond investors seem to be getting into the act. There is an enormous amount of money chasing these sectors and the data to support that follows. First, consider dividend paying stocks. I’ve put together data on fund assets under management (AUM) for the top 5 dividend ETFs. These account for the vast majority of dividend ETF assets. Of course, mutual fund assets are larger, but this data should capture the money flow trends. The chart shows the hockey stick growth of assets both on an absolute basis and compared to SPY assets. When looking at the percentage figures, keep in mind that SPY assets have also grown aggressively recently, having increased by over 28% in the past year and most of that, 21%, in the past 6 months. That’s not bad for a fund that a year ago had $100B.

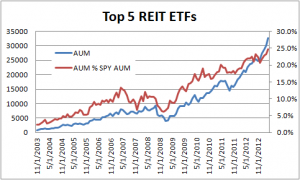

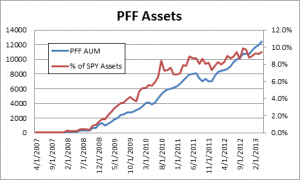

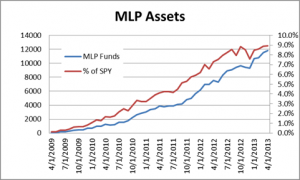

Overall, the top 5 dividend ETF assets has exploded in the past two years to over $50B (incidentally higher than that managed by GLD) – managing 4X the assets as at the end of 2010. Chart data from Bloomberg. REIT ETFs have doubled in size since the end of 2010 from a sizable asset base of $14B. PFF accounts for so much of the preferred ETF market that it is the only fund that I listed. It, too, has more than quadrupled its assets since the end of 2010. MLP assets have grown very quickly to become nearly $12B.

Clearly, an incredible amount of money has been rushed into these yield related stocks in the past two years – just in ETFs alone. But it gets more interesting. Although low volatility investing as a concept has been around for some time, it has recently become very popular. Consider that SPLV, the leading low volatility(LV) ETF, launched in May 2011 and already with over $5B in assets. SPLV’s largest competitor, USMV, was launched October 2011 and now has $3.5B. The Top 5 low volatility ETFs combined are managing $12.6B which is about 9.5% of the size of SPY. These funds have been in such demand that their assets have more than doubled this year (all 5 months of it).

Certainly there is significantly more money than this in the mutual fund complex and under non-categorized active management following low-volatility strategies. But the kicker here is that these low volatility funds look a lot like their dividend ETF competitors. First, they are very heavily weighted in the consumer (combined consumer staples & discretionary) with weightings around 20%, very comparable with dividend funds that have slightly higher concentrations in the mid-20%s and also the SPX. They have higher than SPX weightings in utilities, with dividend ETFs having a typically very heavy 10-30% (with Vanguard having 1%) and LV ETFs having between 9-30% weightings, compared with 3.3% for the SPX. LV ETFs are also very heavily weighted in real estate (including REITs). SPLV accounts for nearly half of LV ETF assets and holds 10% in real estate and the next two holding 7% and 2% respectively vs. 2% for SPX.

Another new, but prevalent trend in investing is called risk parity investing. The idea is, roughly speaking, to allocate assets in a portfolio such that each asset class’s variability (risk) is equal. For example, bonds typically have lower volatility than equities, thus the bond allocation would be levered up until the new allocation had a perceived volatility equivalent to the equity component. Each manager handles this slightly differently. But they might lever up on low volatility equity sectors to match, say, technology shares or the market as a whole. Frankly, it is beyond my capabilities at this time to provide a reasonable metric on how much money is involved in risk parity. There is an interesting discussion about it here and an article here. My feeling is that there are large amounts of assets put to work in this way, but I prefer data to feelings. Input would be very welcome.

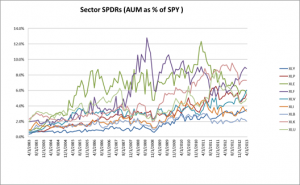

To provide a more complete picture, take a look at this next chart that shows Sector SPDR assets as a percentage of SPY assets. This shows that prior data was not documenting a secular decline in SPY assets relative to other ETFs. One can see that on a relative basis that some sectors have gathered assets and other lost. In particular, it is worth noting that the utilities sector (XLU) has seen a recent and dramatic drop in assets. This is a bit odd since utilities are the poster boy for dividend stocks. It might mean that investors wanted to diversify into a number of dividend payers, presumably for risk reduction. However, recall that utilities represent a significant part of dividend ETF portfolios and the dividend ETFs are far larger than XLU so that even that fraction (as high as 30%) can easily offset (relative) outflows from XLU.

How Much is Too Much?

“The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought, and that’s sort of exactly the Mexican story. It took forever and then it took a night.”

– Rudiger Dornbusch

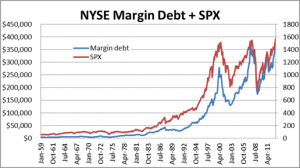

There have been some articles circulating about NYSE margin debt, e.g., here, and I think it is worthwhile to take a look at this. One response to these words of caution was that margin debt as a percentage of stock market capitalization is within a normal range. For myself, I want to put this in context. Here is some data. Note how the drop in margin debt and SPX in both 1987 and 1998 barely register. I wasn’t in the business for 87, but I can assure that the LTCM selloff in 1998 was significant in many ways.

There is a pretty nice correlation of peaks (yes, that’s the technical term) between margin debt highs and SPX highs, followed by steep drop-offs. The conclusion is clear: get short when margin debt peaks. Which leads to the equally clear problem: one can’t tell the peak until afterwards. At least for this data, we can feel comfortable about correlation meeting causation. Leveraged buyers are weak hands because their choice is limited by the margin clerk. Once prices start falling, margin selling leads to further margin selling. To address some concerns about how much margin debt is too much, I’ve created two additional charts that re-slice the numbers a bit.

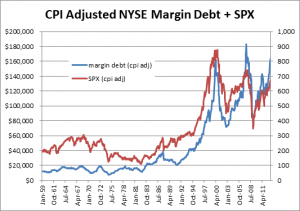

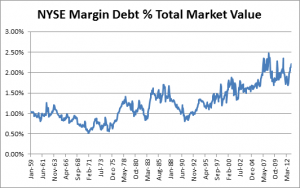

I think that the CPI adjusted margin debt adds some information as it shows that “real” margin debt is about the same as in 2000 rather than being much higher. On the other hand, looking at debt as a percentage of total market capitalization dilutes the information. It shows how the market has become more debt driven than in decades past, but it doesn’t add a red signal at any point. No danger zone for ’87, ’98, ’00, ‘07/08.

What is my conclusion here? Be afraid. Be very afraid. But these things tend to take longer to play out than one expects. In fact, the Rudiger Dornbusch quote from above captures it perfectly. Trades like this get called the widowmaker for a reason. There is evidence of weak hands playing a dangerous game. It would be great if we could find a crowded trade in overpriced assets. Yeah, and then cheap, asymmetric bets to make.

There is more to this story, but it will have to wait for the next post.